Wearing a blue, narrow-brimmed fedora and a white button-up shirt, his hands shaking ever so slightly, Koichi Kashiwa raises his cup to take a sip of coffee as he reflects on his past life running a small publishing firm in Tokyo. This was before the rise of digital media and subsequent decline of the traditional print industry, he says, choosing his words carefully. The 76-year-old suffered a minor stroke last year that affects his mobility. That hasn’t kept him from working, however. He’s off today, but expects a call later in the afternoon from his employer about tomorrow’s eight-hour shift — most likely at a construction site, where he will be deployed to manage traffic.

Some of the how-to nonfiction titles Kashiwa produced during his 30-year career in publishing drew in as much as ¥30 million ($205,700) in royalties, he says. That allowed him to splurge on antiques and other hobbies, but he gradually became careless with his expenses. And a habit he picked up in his 50s — gambling on horses — marked the beginning of the end of his winning streak. His savings dwindled and debt piled up. Tax authorities started seizing his assets. By the time he turned 65, Kashiwa was financially drowning. “I had to do something. I needed to find a source of income,” he says at a crowded cafe in the capital’s shopping and entertainment district of Ikebukuro, the neighborhood where his office used to be situated. “It was hard for someone like me without much else to offer besides experience in publishing to find a job,” he says. “So I became a traffic controller.”

Twilight workers

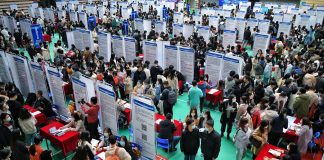

Kashiwa is among millions of Japanese in their golden years earning a living through low-paying, often unstable and physically demanding jobs such as security guards and building cleaners amid a chronic labour shortage in the world’s most rapidly greying nation. While the government has been prodding Japan’s seniors to work longer to help support the social security system under demographic pressure, whether they can maintain their livelihood and motivation under current opportunities are issues that could make or break the economy in the years ahead.

Last month, the ministry of internal affairs announced that those age 75 and older accounted for more than 15% of the total population for the first time, as the ratio of those over 65 hovered at a record 29.1% — the highest in the world. That figure is expected to reach 38.4% by 2065 as the population continues to shrink. Meanwhile, the number of over-65s with jobs grew for its 18th consecutive year, hitting 9.09 million, or 13.5% of the working population. And when looking at those between the ages of 65 and 69, more than 50% are working, according to the report released on Respect for the Aged Day on Sept. 19.

“Most developed economies are aging, but not as quickly as Japan,” says Miho Fujinami, an associate professor at Chiba Keizai University and an expert on elderly employment. “At the same time, statistics have shown that the willingness to work among older Japanese is higher than some Western nations.” According to the Cabinet Office’s Annual Report on the Aging Society for fiscal 2021, the percentage of those age 60 and over in paid employment who wished to continue working was 40.2% in Japan, higher than the three other nations surveyed: the United States, Germany and Sweden.

That desire to continue being a part of the labour force concurs with the government’s emphasis on what it calls the “100-year-life” and its push for related labour market reforms aimed at allowing people to work well into their twilight years to compensate for the nation’s stubbornly low birth rate and ballooning health care and pension costs. While most Japanese companies have set their mandatory retirement age at 60, a revision to a law concerning senior employment that came into effect in 2013 now requires firms to allow employees to work until 65, the year people become eligible to receive public pension benefits. That was further amended last year to encourage businesses to secure opportunities for their employees to work until they reach 70, either by abolishing or raising the retirement age, rehiring employees on post-retirement contracts or commissioning individuals for certain tasks.

Fewer jobs for life

Behind these measures is Japan’s famously high life expectancy and the specter of the nation’s lifetime employment scheme, which ensured generations of workers financial security through a seniority-based wage system while offering companies a dedicated pool of corporate warriors. While being credited as one of the biggest drivers behind the nation’s post-war economic miracle, the custom has come under increasing scrutiny in recent years for hindering labour market mobility amid intensifying global competition for talent, and has been deemed unsustainable by many business leaders.

The fact remains, however, that many older workers have little experience outside of the roles they assumed in their respective companies, a major disadvantage once they’re thrown into the labor market. Indeed, 76.5%, or 3 out of 4 people age 65 or older on payrolls in 2020 were hired in low-paying, irregular jobs, a head count that grew by a whopping 2.27 million from a decade earlier. “Japan’s rigid job market makes it difficult for older workers to find new jobs,” Fujinami says. “That’s why the government’s policy focuses on keeping employees working within their companies rather than encouraging them to seek work elsewhere.”

But for many, like Kashiwa, who were self-employed or had to leave their jobs for one reason or another, that’s not an option. And for older workers struggling to find employment, choices can be limited. There are approximately 590,000 keibiin, or security guards, in Japan, a broadly defined job that includes personnel tasked with patrolling facilities as well as traffic controllers such as Kashiwa. It’s a high-demand occupation that has seen its numbers steadily grow over the years amid an ongoing construction boom. Sixty-four percent of workers in this sector are over the age of 50, however, while almost 18% of them are 70 or older, according to the National Police Agency.

It’s a tough job even for younger workers, requiring patience and stamina to direct traffic and pedestrians while standing for hours on end, rain or shine, by construction sites and building facilities. “I earn around ¥180,000 a month, working five or six days a week,” says Kashiwa, a shortish man with an easy smile. “I guess my annual income comes to around ¥2 million, which is around one-seventh of what I used to make when I was a publisher.”

According to the 2018 National Survey of Living Standards, 36.3% of older households had annual incomes of less than ¥2 million, and 12.3% below ¥1 million. That’s compared to around ¥5.5 million for an average household. In 2019, a panel report by the Financial Services Agency estimated that a couple who will live until 95 years old will need at least ¥20 million more than what their pension benefits will provide as the nation rapidly ages. While the government effectively withdrew the report and played down this figure, it nevertheless fueled people’s anxiety over their future.

Tomohito Tanaka, a sociologist and associate professor at Sendai University, worked part-time as a security guard while attending college, eventually spending a total of 10 years on and off in the occupation as part of his field work into the job and industry. “Even back when I started as a security guard 20 years ago, most workers were much older than I was,” Tanaka says. ”People came from all walks of life — some had been laid off and couldn’t find another stable job. Others had retired but felt they still had the energy to work. “For older people looking for work, security guards, cleaners and apartment caretakers have become go-to destinations.”

Senior employment havens

Tetsuro Kanzaki, a stout, bespectacled 67-year-old with gray, thinning hair, made his debut as an apartment superintendent a decade ago after leaving his job at a foreign-owned medical supply firm. He now works six days a week at a 24-story residential highrise in central Tokyo, from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. on weekdays and from 8 a.m. to noon on Saturdays. His routine involves inspecting and cleaning the apartment building and its facilities, as well as dealing with residents’ inquiries and any other issues that arise in the property.

Kanzaki, who doesn’t have children and lives with his wife in neighboring Chiba Prefecture, says this is the third apartment building he has overseen since he began working for Mitsui Fudosan Residential Service Co., the property management arm of major real estate developer Mitsui Fudosan Co. The firm currently hires more than 1,350 caretakers such as Kanzaki, who works for a monthly salary of ¥180,000, excluding commuting expenses.

According to the national census, there were around 150,000 such caretakers in 2015, with their average age being 53½ years old. Most work part time or are hired on a contract basis. Besides financial insecurity, Kanzaki believes another reason so many elderly opt to work in Japan is because “retirees often find themselves with all the time in the world, but with little to do without hobbies and friends.”

“I feel that’s a big difference in attitude compared to Western nations, where people typically look forward to retirement and the freedom associated with it,” Kanzaki says. However, there is a limit to how long one can work. For Mitsui Fudosan Residential Service, 72 is retirement age for its superintendents, which can be extended for a maximum of three years. “Still, the age of applicants have really gone up these past several years,” says an official at the company’s human resources department. “An 80-year-old person even recently applied for a job as a caretaker,” he says. “Meanwhile, the competition for hiring those in their early 60s is becoming intense as that’s the age many workers retire and begin to look for new opportunities.”

The price of longevity

In his first policy speech since taking the helm of the government last year, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida laid out his growth strategy, with one of his pillars aimed at “putting to rest people’s anxiety about the era of 100-year lifespans” and the various strains longevity can force on society. “We will make social security and the tax system neutral with regard to ways of working and endeavor to make universal workers’ insurance a reality,” Kishida said. “Looking ahead, we will work to build a social security system oriented to all generations in which all people, from children and those raising a family to the elderly, can feel assured.”

Japan TImes